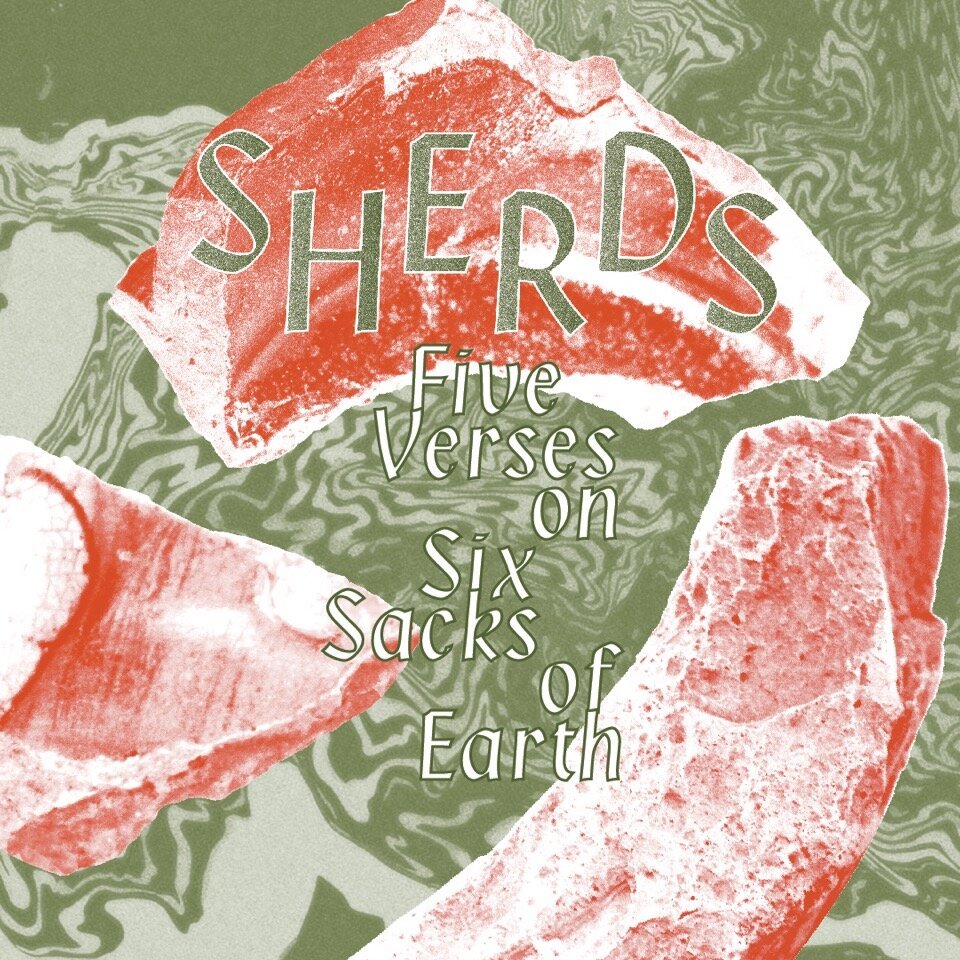

Rebecca Lee and Nastassja Simensky - SHERDS

Primary residents Rebecca Lee and Nastassja Simensky present a version of SHERDS for Montez Press Radio. SHERDS is an experimental audio work based on a six-week archaeological dig which took place at Malkin Tower Farm in Pendle, during the hot summer of 2018. Performed by an ensemble of musicians, archaeologists and vocalists, SHERDS brings together spoken word, improvisation, vibrating rocks, field recordings, live audio and new compositions to form a shifting soundscape. The 90-minute programme draws on the specialisms of each of the ensemble to collapse, unearth and reassemble the rhythms and processes of archaeological excavation, changing land use, topography and her story.

On the occasion of the presentation of the work through Montez Press Radio Rebecca and Nastassja share a research-based text providing insight into the development of SHERDS.

TEXT

Bastard Trowel: Labour and collaboration on an archaeological dig

Sherds is an ongoing experimental work initiated on a residency during a five-week archaeological dig. Performed by an ensemble of musicians, archaeologists and vocalists, SHERDS exists as a live performance, a collection of writing and a 90-minute audio work. The most recent audio iteration brings together spoken word, improvisation, vibrating rocks, field recordings, live audio and new compositions. Exploring new forms that radio broadcast affords, SHERDS draws on the specialisms of the extended ensemble of performers and archaeologists to unearth, collapse, backfill and reassemble the rhythms of archaeology, changing land-use, topography and history.

---

The Pendle witch trials are well documented in popular culture, local history and legal documents from the 17th Century. The ‘Witch Way’ bus service that runs from Burnley to Manchester, through Pendle, sports the image of a blonde woman in a sweetheart-necklined dress on a broom, whilst a local public sculpture, rendered in steel with a green and raw umber patina, depicts a woman in early modern dress and chains. Neither of these representations of ‘witches’ begin to acknowledge or present the very real people who were charged and tried for witchcraft in 1612 or the conditions in which they were living. During the 17th Century, the landless poor, and in particular women with no familial support, would have sold their labour and knowledge of herbs and remedies, mending and repairs, midwifery, spinning, dyeing to sustain their livelihoods and independence.

In the summer of 2018, an archaeological dig took place at Malkin Tower Farm near Blacko in Pendle. We joined the dig for five weeks as artists in residence. Local historians and archaeologists used geophysical surveys to locate the field that most likely contained historical features and material culture, that might illuminate what everyday life was like for the landless poor in 17th century Pendle – in particular the lives of the people accused of witchcraft in the 1612 trial. Malkin Tower Farm was chosen for the excavation because of reference to ‘Malkin’ in historic written accounts of significant political and social change during the 1600s. At the time of the residency, silage was growing in three of the four fields. A group of student archaeologists and a robust lamb named Larry occupied the other. It was almost unbearably hot. We could see smoke rising from the summer fires clawing their way across nearby Winter Hill, devastating the nests of the curlew and other ground-nesting birds, reptiles and peat cover. As a thousand years of peat burned over those 41 days, the market price of silage increased, reminding us of the precarity and speculation of current farming practices. Malkin Tower Farm, like many other hill farms, had diversified their labour and income. We were sleeping in their smallest holiday cottage - a neat studio-bedroom in a converted piggery.

From the farm we could view the broader landscape surrounding the excavation and the urban areas in the valley below, towards Nelson and Colne. These made visible ongoing changes to the hillside. We were both interested in making work that looked at history and changing land use in new ways. This included not just what the archaeologists found in the trenches, but how they went about doing their work and what it was like to take part on an archaeological dig on a working farm. We wanted to work alongside the archaeologists. This included witnessing the effects of working long hours in all weather conditions, and listening to how their own expectations of their work and what they might find changed over the course of excavation.

The dig at Malkin Tower Farm, July 2018. Image credit Nastassja Simenksy

“There were dynamics on the site that were complicated but beautiful friendships were formed from it too.. but the thing that you don’t stress about this is how hot it was. You mention it but...if you could turn the temperature up in here [Nottingham Contemporary] so that we were all sweating and trying to strip off and you can’t get cool, that would bring you into the environment - it was so hot. But I think that helped build up more relationships because we were all in a circle together and a few of us ended up very ill. But that’s archaeology [1].”

Two rectangular trenches were dug by academics and student archaeologists from University of Central Lancashire and a group of anthropology and archaeology students from several universities in the US. The process was drawn out - slow digging, bent over, heatstroke, observation, hard and weird graft, dwelling, temporary accommodation, expending emotional labour and energy. For the archaeologists, it was hard physical work on site, as well as a process of adjusting to living with a group of new people, preparing meals together, before returning to clean artefacts and make charts.

The archaeologists considered themselves to be actively participating in history as a process - remaking history as they excavate. Lead archaeologist Rick described how the networks and connections that existed in the past also involve us [people working within historic disciplines] now, so when we carry out archaeology and fieldwork we are participating in an ongoing set of processes in the present, looking at and interacting or thinking with the landscape and how we relate to it. Working in the landscape and comprehending it in this way, archaeologists undertake a form of dwelling, like the people they are studying would have done.

“Successful historical writing requires research of facts, presented with balance and accuracy. Yet to fairly read history we must build networks of understandings that link seemingly innumerable factors often requiring interpretation and imagination [2].”

Immersing ourselves in the flow of the dig, we explored creative ways of recording what was happening as well as talking to local people about what the Pendle landscape and local history meant to them. Using different kinds of microphones and cameras we documented the conversations, tools and methods of the archaeologists, as well as the presence (and sometimes the lack) of human-made structures, vegetation and animals. Archaeologists Catherine, Danielle and Rick were key influences and helped us understand the subjectivity of archaeology and the physical, emotional and cognitive labour involved in this work. Catherine is a Canadian historian and archaeologist who took part in the dig to reconnect to her Yorkshire ancestry and family whilst attempting to understand the social and political side of the Pendle witch trials and changing public opinion of the landless poor at that time. In the score for the performance, we deconstructed a popular 17th century ballad about transgressive women, and reused it to create a shifting background to Catherine's story about ancestry, superstition and pragmatism.

The dig at Malkin Tower Farm, July 2018. Image credit Nastassja Simenksy

Along with Catherine’s story, four other points of reference emerged over our weeks working on the dig, and informed the content of SHERDS: A Milk Bowl, Greg (grit stone), Hawthorn and Curlew. These waymarkers, which became the five verses in the piece, provided us with a way to share distinct perspectives on the historic, contemporary and future significance of the excavation and this location through materials, landscape, the process of archaeology, labour and time. We drew on the material sounds and recordings of the site, as well as the dig data, researched the history and folklore of the area and brought in the archaeologists’ own stories of working in the heat in the landscape to develop starting points for the music and libretto.

Hawthorn is an ancient tree standing in an exposed position at the top of Malkin Tower Farm surrounded by a dry stone wall; a witness to the changing industry and living habits in the valley and a knowledgeable inhabitant of the hillside. We used the resonance of wire fences and creaking branches around the field to create chords for a musical composition. The singers performed this composition as the slow, half sung, half spoken voice of Hawthorn. The endless wind and the sympathetic, supple limbs of the tree also appear as live, improvised duets with the field recordings we made. Local historian John Claydon, spoke to us about how this hawthorn was once one of many trees in a medieval field boundary, and through conversations with him on the dig we realised that John’s voice should emerge through and alongside that of the hawthorn and musician Bobby Cotterill.

Ceramic sherds were plentiful once the archaeologists had removed turf, top soil, night soil and rubble. Rick described how finding a piece of thrown pottery was like discovering a slice of time. From a close examination of that single piece, one can imagine the width, depth and purpose of the original whole; archaeological imagination filling in the gaps. The shape of a milk bowl, shallow and broad to keep its contents cool, suggested the daily processes, rituals and utensils that a family might once have used on that site. For us, this fragment presented a way to suggest the presence of the women who raised families, worked on the land and supported communities. We wanted to imagine that this fragment, dug from the trench, could be reformed again as a bowl through a repetitive, layered and shifting vocal score and solo vocal utterances that were improvised live by Caroline Trutz, who handled, and ‘read’ fragments of pottery like they were ceramic scores.

“It’s a thing that is often said, but if we don’t know what something is, we say it’s ritual...I’m sure you’ve seen Time Team and things like that... I think the ritual element of this is important. A lot of the time when we find something, you know, if it’s out of context or if it’s unusual, we just assign it this ritual character, so I think bringing that out is quite good. I was interested in the first part with the Milk Bowl. This almost fetishisation of an everyday item. Which is basically what archaeology is; it is fetishising the everyday. A milk bowl is just something that someone uses and they throw away and don’t think about it. But then we find it and we turn it into something much bigger than it was [3].”

Sherds Performance, Nottingham Contemporary, January 2020. Image credit Reece Straw

Through the course of the project, we explored the varied temporalities and scales at play in Pendle. The final verse is a song for the curlew, a bird we saw and heard a lot from the trench and on the Pendle moors. The curlew scans the landscape with a level of detail and scale beyond the mapping and geophysical surveys of the archaeologists. The words of this verse refers to the impact of the unusually hot summer in 2018 on moorland plants, peat fires, the stock prices of silage, the working conditions on the dig and the nesting sites of the curlew. The plight of the curlews during that particular summer resonated with the voice of the bird, which we heard during the drawn out processes of making field recordings, and to us sounded both haunting and vulnerable (folklore describes ‘the curlew’ as a bringer of bad fortune or stormy weather). The distinctive two tone ‘coor-lee’ call was brought into the performance through the call and response of the bassoon’s fragmented and faint multiphonic notes, together with Alison Cooper's quivering, rising vocals.

Greg (grit stone) is the verse which reveals the process of finding an important artefact and is central to the piece. A large structural grit stone was the most significant find and was affectionately named ‘Greg’ by the students. The stone connected us to the even longer timescales of geological formation but also, to the destructive nature of archaeology. Archaeologists meticulously dig down, context by context, moving back in time. As they excavate deeper into the past, the more recent earth, artefacts and features are removed before being cleaned, documented and logged on context sheets and in site reports. This slow moving verse mimics the strata of soil or rock, with Kelly Jayne Jones working with amplified rocks and electronics. Sophie Cooper’s trombone solo attempts to convey the slow vibrations of the geologic, reverberating through the space, almost making the air solid with the thickness of time and sounding the eventual splintering of the rock. The smooth flat grit stone was once a post pad, and thus represented a significant discovery because it provided evidence to suggest there had been a grainstore or dwelling on the site. Archaeology is preservation through record. The looped, fragmented and layered vocals that close this verse serve to trace, retrace and reform the findings of the dig, much like the laborious sketching and recording processes that only rarely present a coherent whole.

“There’s humour as well: at one point the ensemble persistently sings ‘bastard trowel’, reworking the frustrations of a weary archaeologist. At another moment, the frustration turns to wry hope as a refrain informs us of the discovery of ‘Something like a pipe, something like a fragment of milk bowl’ before adding that ‘Some more of it would be helpful.’ Funny though these moments are, they also ground the work in Lee and Simensky’s interest in labour: Sherds has clear roots in the hot, frequently frustrating dig itself. The production of history, like the production of music, is hard work [4].”

Image 4, Sherds Performance, Nottingham Contemporary, January 2020. Image credit Reece Straw

We consciously brought together an ensemble with distinct approaches to performance. As described above, each musician took on a specific expressive role in relation to the sections and verses of the piece. In preparing this work for a staged performance, it was important for us to find a way not only to convey the complexities of the excavation through vocals and music, but also to reveal, where possible, the labour of bringing them into being. Caroline, whilst singing from the ceramic sherds, is filmed by another performer and her image is projected onto tarpaulins high above the performance. At another point, the singers use tuning forks on stage to find their pitches, the functional tools forming a counterpoint reminiscent of the ring of trowels on stone.

The practical aspects of the dig informed the set, props and costumes and so the design extended our collaboration with the site and archaeologists. Rather than treat the necessary lugging of props, equipment and people as discrete, we worked with a choreographer to foreground this activity. We considered the stage to be a world within a world, a space where the dig continued, out of place and time, on an altogether different visual and temporal register. All of the performers and everything that constituted the work remained on stage throughout the performance, incorporating the cycles of rest and work throughout. All aspects of the archaeologists’ work, as well as their social and material needs were centred, for the most part, in one field. Just like the field of the dig which encompassed multiple concurrent time frames, SHERDS does not aim to tell a narrative story of an archaeological dig, but instead combines and disrupts the chronology of the excavation - where temporalities are collapsed and interwoven.

The work’s fragmented and rhythmically varied quality captures something of the rhythms of the site. Rather than uncovering a coherent history, partial slices of different eras and timescales imbricate one another…[Lee] and Simensky sought to ‘have all of the historical moments/events present at the same time without blending them’. It’s successful, and a highly effective way of capturing something of the spatial and temporal complexity of an archaeological dig, in which the social, economic, ecological and geological relations of various moments in history collide at a particular place at a particular moment.[5]

[1] Archaeologist Danielle Knights, Sherds post performance Q&A, Nottingham Contemporary, 2020

[2] Guy, N. ‘After Lolly Willowes, For All The Aunts’, 2021

[3] Archaeologist Katy Soar, Sherds post performance Q&A, Nottingham Contemporary, 2020

[4] Bell, D. ‘Capacious Composition, an interview with Rebecca Lee’, British Music Collection, 2021

[5] Bell, D. ‘Capacious Composition, an interview with Rebecca Lee’, British Music Collection, 2021

SHERDS was written and produced by Rebecca Lee and Nastassja Simensky. Performed by Alison Cooper, Bobby Cotterill, Caroline Trutz, Kelly Jayne Jones, Nastassja Simensky, Rebecca Lee, Sophie Cooper, Rebecca Atherton and Bernie Velvick. With the voices of archaeologists Danielle Knights, Katy Soar, Catherine Reardon, Rick Peterson and Aidan Parker and local historian John Claydon.

Rebecca Lee is a musician and composer producing performances and projects with a focus on narrative form and ways that musical materiality can intervene with place. She values collaboration and draws on historical and contemporary processes.

Nastassja Simensky is an artist based in Nottingham and Essex. Nastassja works with particular geographies where complex issues around history and heritage, power and governance, ecology and the geopolitics of extraction are crystallised.

Montez Press Radio is an experimental broadcasting and performance platform, founded in 2018 with the goal of fostering greater experimentation and conversation between artists, writers, and thinkers through the medium of radio.